Hawala: The Invisible Bank: The centuries-old trust network that still moves billions across borders with no paperwork and no app

Writer Wills Mayani

From Somali remittances to Afghan markets and Western terror investigations, hawala operates as the world's oldest parallel financial system — informal, resilient, and still moving billions outside the view of modern banking.

A transfer with no trail

On a cold afternoon in Minneapolis, a Somali-American taxi driver walks into a small storefront wedged between a halal butcher and a travel agency. The signage in the window advertises phone cards and international shipping. There is no marble counter, no glass partition, no queue machine dispensing numbers. He hands over $300 in cash. The man behind the desk writes something in a notebook, makes a phone call, and nods.

By evening, his mother in Garowe has the money.

No wire confirmation. No SWIFT code. No routing number. No app notification.

The transaction exists only in trust and in memory.

This is hawala — an informal value transfer system that predates modern banking by centuries and, despite decades of scrutiny, still moves billions of dollars across borders every year.

In parts of Somalia, Afghanistan, Yemen and rural Pakistan, hawala is not an alternative to banking. It is the banking system.

Before banks, there was trust

Hawala’s origins trace back more than a millennium to trade routes stretching across South Asia, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa. Long before central banks, before correspondent banking networks, before digital clearing houses, merchants needed a way to move value without physically transporting gold or silver across dangerous terrain.

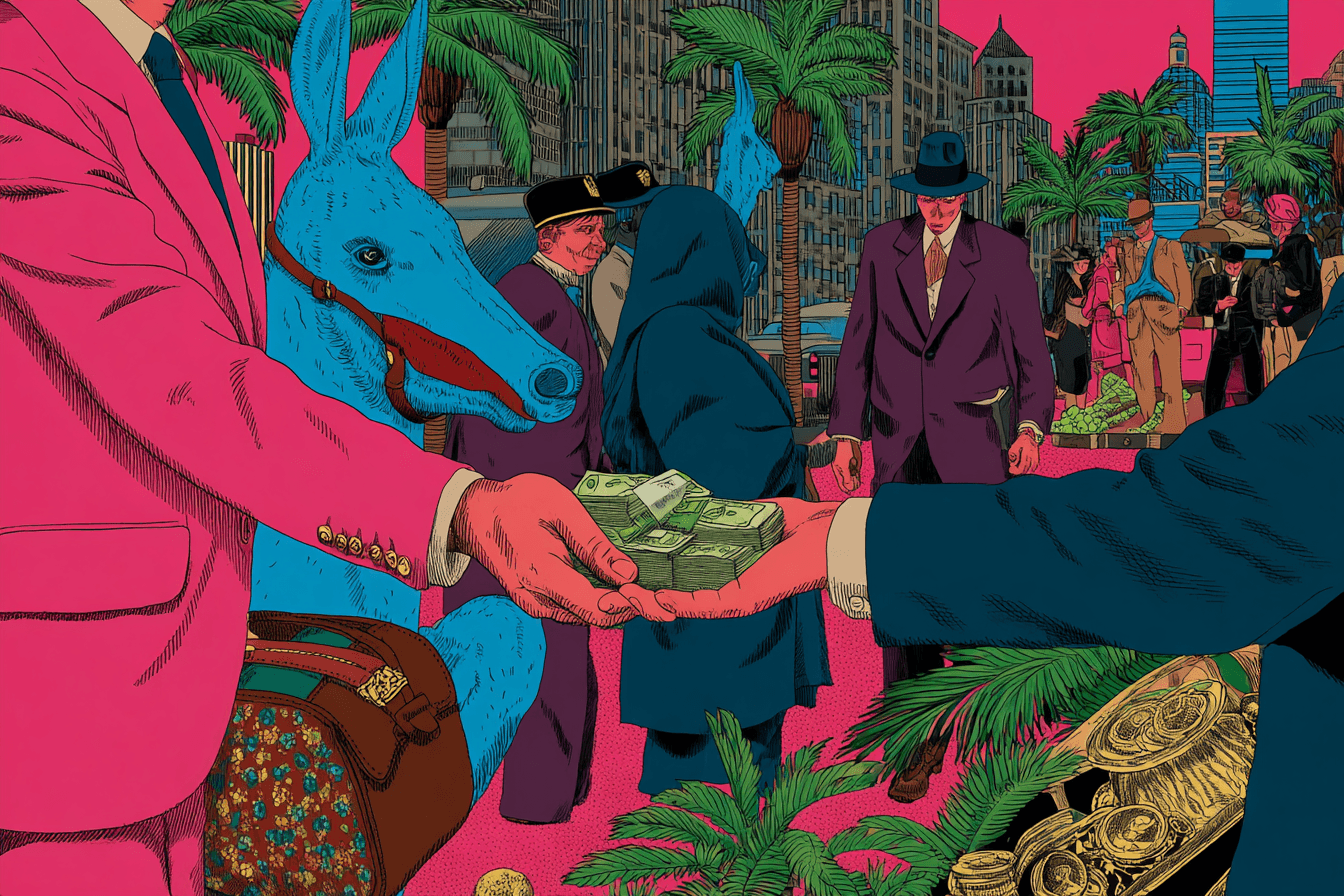

The mechanism was simple. A trader in one city would give money to a trusted broker. That broker would communicate — often by coded letter or messenger — with a counterpart in another city, who would pay the intended recipient. Debts between brokers would later be settled through trade goods, offsetting transactions or periodic balancing.

No money crossed borders in the way modern regulators understand. Value did.

The system relied on honour codes, clan affiliations, merchant reputation and community enforcement. A hawaladar who defaulted would not merely lose money; he would lose social standing and future business across an entire network.

Centuries later, the core mechanics remain largely unchanged.

How it works

At its most basic, hawala functions through paired brokers.

A customer gives cash to Hawaladar A in one country. Hawaladar A contacts Hawaladar B in the recipient country — traditionally by phone, now sometimes through encrypted messaging or private digital ledgers. Hawaladar B pays the recipient from his own cash reserves.

No funds are physically transferred at that moment. Instead, Hawaladar A now owes Hawaladar B. Over time, these imbalances are reconciled through trade flows, bulk settlements, or reverse transactions moving in the opposite direction.

In diaspora-heavy corridors — Minneapolis to Somalia, Dubai to Kabul, London to Mogadishu — these flows are constant and bidirectional. Debts often cancel out organically.

The system is fast, cheap and flexible. Fees are typically lower than formal remittance channels, and documentation requirements minimal. Identification standards vary by jurisdiction, but in many contexts, familiarity and community ties substitute for bureaucratic verification.

From a regulatory standpoint, that is precisely the problem.

The remittance lifeline

In Somalia, remittances account for an estimated $1.5 to $2 billion annually — roughly a quarter of GDP by some estimates. Around 40 percent of Somali households receive money from relatives abroad. These transfers fund school fees, rent, medical bills and food.

Formal banking infrastructure in Somalia remains limited. Decades of civil conflict and institutional collapse eroded public trust in state banking institutions. International banks, wary of anti-money laundering compliance risks, have repeatedly “de-risked” by severing correspondent relationships with Somali money transfer operators.

When Western banks close accounts to avoid regulatory penalties, the impact is immediate. Remittance companies struggle to access dollar clearing systems. Diaspora communities panic about interruptions. Humanitarian agencies warn of economic shock.

In 2013, Barclays’ decision to close accounts of several UK-based Somali money transfer operators triggered a diplomatic crisis. Aid agencies argued that cutting off hawala channels would devastate ordinary families far more effectively than any targeted sanction regime.

The paradox is stark: the same system Western governments scrutinise for opacity is the mechanism keeping fragile economies alive.

Afghanistan’s parallel finance

Afghanistan offers a similar case study, though under very different political conditions.

Before and after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, hawala has functioned as the country’s financial bloodstream. Estimates suggest that up to 80–90 percent of financial transactions in Afghanistan have at times passed through hawala networks rather than formal banks.

Part of this reliance stems from geography. Rural communities lack access to bank branches. Part stems from mistrust in formal institutions. Part stems from sanctions and international isolation, which complicate cross-border banking operations.

In Kabul’s Sarai Shahzada market, dozens of hawaladars operate in close proximity, their offices modest but busy. Transactions can involve small remittances or multi-million-dollar commercial settlements. The system handles everything from migrant transfers to large-scale trade finance.

Western security agencies have long suspected that hawala networks can facilitate the movement of funds for insurgent groups. Yet attempts to dismantle the system outright have repeatedly proven counterproductive, pushing flows further underground rather than eliminating them.

Post-9/11 suspicion

After the September 11 attacks, hawala became synonymous in Western media with terrorism financing. Investigations revealed that some al-Qaeda operatives had used informal value transfer systems to move funds discreetly across borders.

Governments responded with aggressive regulation.

In the United States, informal money service businesses were required to register under federal law. Anti-money laundering (AML) frameworks tightened. Suspicious activity reporting expanded. International cooperation intensified.

In principle, hawala is not illegal in most Western countries if properly registered and compliant with financial regulations. In practice, compliance burdens can be onerous for small, community-based operators. Many struggle to access banking services needed to operate legally, particularly in high-risk corridors such as Somalia.

This dynamic creates a cycle. Regulators impose strict compliance requirements. Banks, fearing penalties, withdraw services from small remittance firms. Informal channels expand to fill the vacuum.

Criminal misuse is possible. But blanket suppression risks collateral damage to entire communities.

The Minnesota investigation

In 2024 and 2025, federal investigators in Minnesota examined whether funds from a large welfare fraud case may have been transferred through hawala networks, potentially reaching overseas extremist groups.

The headlines were predictable: informal money transfer, Somali diaspora, terrorism financing.

But the deeper issue was more complex.

Hawala does not inherently generate crime. It transmits value. Like any financial system — including formal banking — it can be exploited if oversight fails. The challenge for regulators is distinguishing between illicit use and legitimate remittance activity that sustains families.

Sweeping crackdowns risk criminalising entire communities whose reliance on hawala is rooted not in malice but in necessity and historical practice.

The political optics are volatile. The policy trade-offs are real.

Digital evolution

Hawala is not frozen in the medieval past.

Mobile money platforms in East Africa, particularly in Somalia and Kenya, have layered digital infrastructure atop traditional trust networks. Some operators maintain encrypted digital ledgers rather than handwritten notebooks. Messaging apps facilitate cross-border communication between brokers.

In certain contexts, extremist groups have reportedly experimented with digital variants of informal transfer mechanisms, blending mobile payment systems with trust-based clearing arrangements.

Yet the core logic persists: value is moved through relationships, not through centralised clearing houses.

In an era dominated by fintech branding, hawala represents something older and quieter — an unbranded financial architecture embedded in community.

Why it survives

Modern banking prides itself on transparency, compliance and scale. Hawala competes on trust, speed and accessibility.

For migrant workers sending small sums home, bank transfer fees and exchange rate spreads can be punishing. Documentation requirements can be intimidating. In fragile states, formal banking systems may be unstable or inaccessible.

Hawala offers simplicity.

You walk in. You hand over cash. The money arrives.

There is no onboarding journey. No app update. No biometric verification.

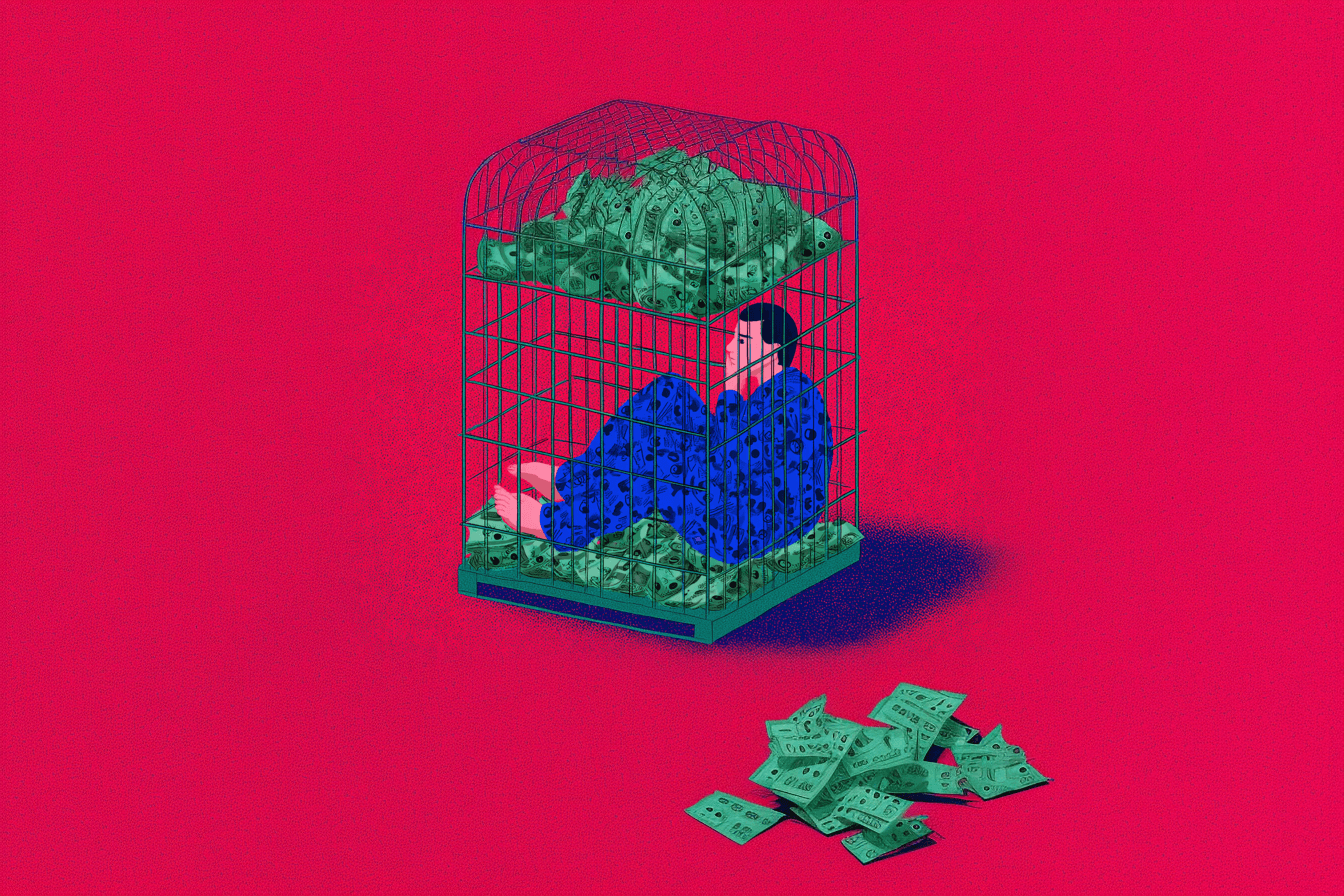

Its resilience lies in its social foundation. Where formal institutions are weak, interpersonal networks compensate. Reputation becomes enforcement. Community becomes collateral.

The moral tension

For policymakers, hawala presents an uncomfortable dilemma.

On one hand, informal systems lacking comprehensive audit trails create vulnerabilities for money laundering, sanctions evasion and terrorism financing. Financial transparency is a cornerstone of modern regulatory regimes for good reason.

On the other hand, cutting off hawala channels can devastate economies dependent on remittances. When formal banks retreat from high-risk jurisdictions, informal networks often become the only viable conduit for humanitarian and family support.

The question is not whether hawala is perfect. It is whether suppressing it improves outcomes.

In Somalia, remittances frequently exceed foreign aid flows. Disrupting hawala would not primarily hurt armed groups. It would hurt households.

The invisible scale

Precise global figures are difficult to establish because hawala, by definition, does not produce centralised transaction data. However, analysts and multilateral institutions estimate that informal value transfer systems collectively move tens of billions of dollars annually.

These flows intersect with formal systems at various points — when hawaladars settle imbalances through trade, currency exchange or bulk transfers via banks in third countries.

Hawala is not entirely outside global finance. It exists in the margins, intertwined but not fully integrated.

It is invisible only to those who do not depend on it.

Regulation without destruction

Some governments have attempted to strike a balance.

The UK has run registration campaigns encouraging informal money service businesses to formalise under HMRC oversight. International bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) have emphasised risk-based approaches rather than blanket bans.

The aim is to increase transparency without erasing access.

Whether this balance is achievable remains contested. Compliance regimes are expensive. Smaller operators may close rather than adapt. Larger, better-capitalised firms may consolidate the market, potentially weakening the hyper-local trust networks that define hawala’s character.

Formalisation can bring legitimacy. It can also change incentives.

The oldest fintech

In a world obsessed with blockchain, decentralised finance and frictionless digital payments, hawala appears almost archaic.

Yet it shares certain philosophical traits with modern decentralised systems. It operates without a central authority. It relies on distributed trust. It settles imbalances through networked relationships rather than a single clearing house.

It is, in some respects, the oldest form of peer-to-peer finance.

The difference is that its ledger lives in human memory and social obligation rather than code.

An invisible institution

The Minneapolis taxi driver does not describe himself as participating in a shadow financial system. He describes himself as sending money home.

His mother does not experience the funds as an abstract remittance statistic. She experiences them as rent paid, food purchased, a child’s school uniform secured.

To regulators, hawala is a compliance challenge.

To economists, it is an informal remittance corridor.

To millions of families, it is infrastructure.

The invisible bank persists not because it resists modernity, but because it fills gaps modern systems have not fully addressed.

It is easy to criminalise what operates beyond paperwork.

It is harder to replace what operates on trust.

And as long as formal finance leaves space unserved — whether through cost, exclusion, sanctions or institutional fragility — hawala will continue to move quietly through that space, transferring value across borders without an app, without a trail, and without disappearing.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.