Lebanon's Infinite Crisis, Explained: How a country's currency lost 98% of its value and daily life just… continued

Writer Wills Mayani

Since 2019, the Lebanese pound has collapsed by more than 98%, banks have frozen savings, electricity has largely vanished and yet daily life persists. How does a country absorb economic freefall and keep moving?

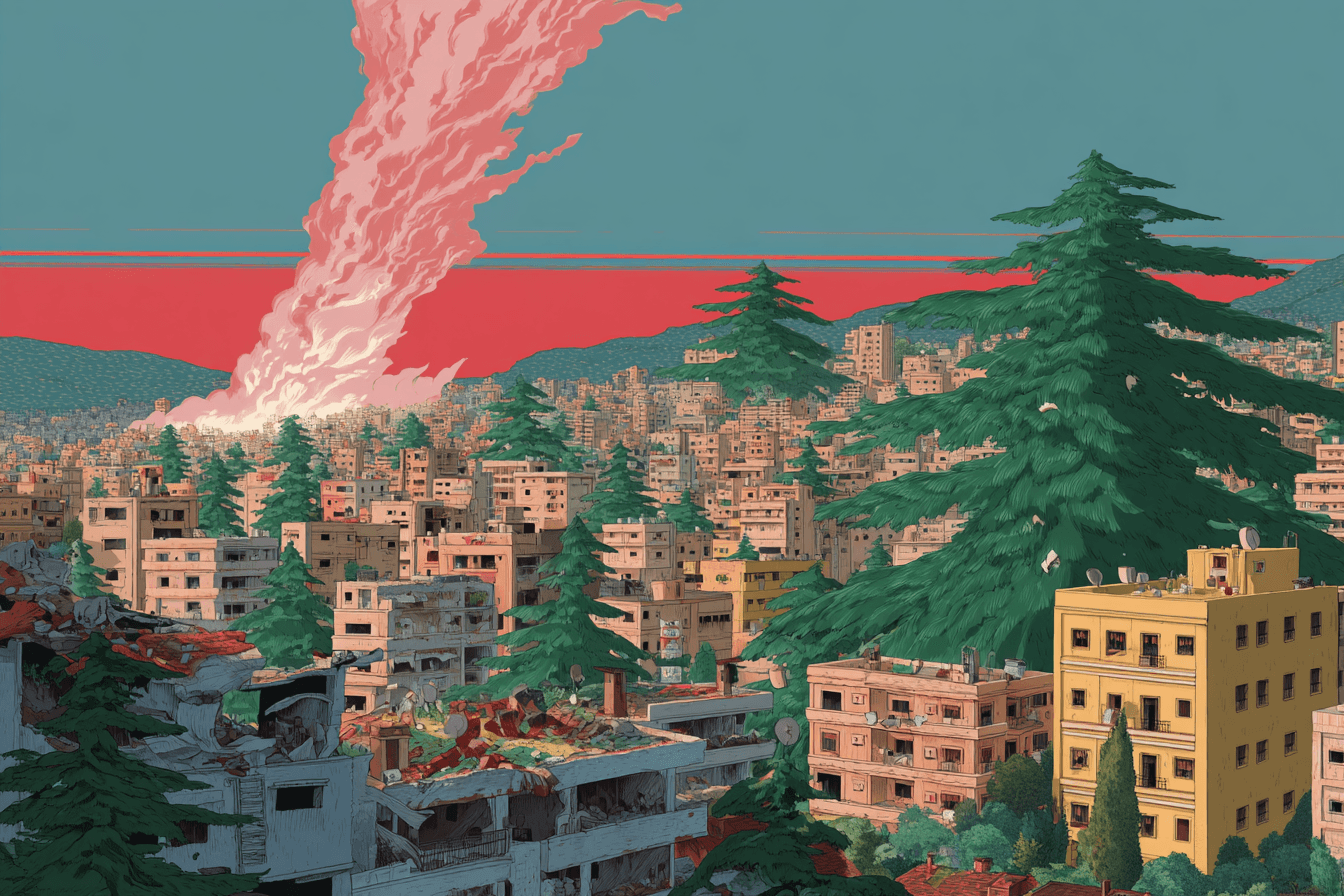

A collapse without a climax

In most countries, a currency collapse of 98 per cent would signal the end of something. A government would fall. The army would intervene. Shops would close. Supermarkets would empty. There would be a date historians could circle and label as rupture.

Lebanon offers no such clean break.

Since 2019, the Lebanese pound has lost more than 98 per cent of its value against the US dollar. What had been fixed at 1,507 to the dollar for over two decades now trades in the tens of thousands. Wages once denominated in pounds have evaporated in real terms. Bank deposits — the savings of a generation — were effectively frozen overnight. Electricity from the state grid dwindled to near-zero. The middle class disintegrated. The World Bank described it as one of the worst economic crises globally since the mid-19th century.

And yet, Beirut still hums. Cafés still open. Weddings still happen. Traffic still snarls along the coast road at sunset.

The crisis did not explode. It settled.

How the model broke

To understand how daily life continues, one has to understand how it was structured in the first place.

For years, Lebanon operated on a financial model built on confidence rather than production. The country imported far more than it exported and relied heavily on remittances from a vast diaspora. Dollars flowed into local banks, attracted by high interest rates. The central bank maintained the currency peg through increasingly complex financial engineering, offering ever more generous returns to banks to keep dollars circulating.

Economists would later describe it as a form of state-sponsored Ponzi finance. As long as fresh dollars entered the system, the illusion held. When inflows slowed — due to regional instability, declining investor confidence and political paralysis — the structure cracked.

By late 2019, protests erupted across the country over new taxes and entrenched corruption. Within weeks, banks imposed informal capital controls. Depositors could not access their savings. Transfers abroad were halted. Trust — the invisible pillar of the entire model — collapsed.

Once confidence leaves a banking system, it rarely returns quickly.

The arithmetic of 98 per cent

Currency collapses are abstract until they are not.

A salary that once equated to $2,000 per month shrank, in real terms, to a fraction of that amount. Teachers, civil servants, doctors and soldiers saw their purchasing power evaporate. Imported goods — fuel, medicine, wheat — became prohibitively expensive. Inflation soared into triple digits.

Yet the numbers only tell part of the story.

Lebanon is heavily dollarised. Long before the crisis, rents, cars and private school fees were often priced in dollars. As the pound deteriorated, businesses gradually shifted to quoting prices directly in US currency. Supermarkets labelled shelves in dollars. Restaurants printed menus in dollars. A parallel economy emerged, half-formal, half-improvised.

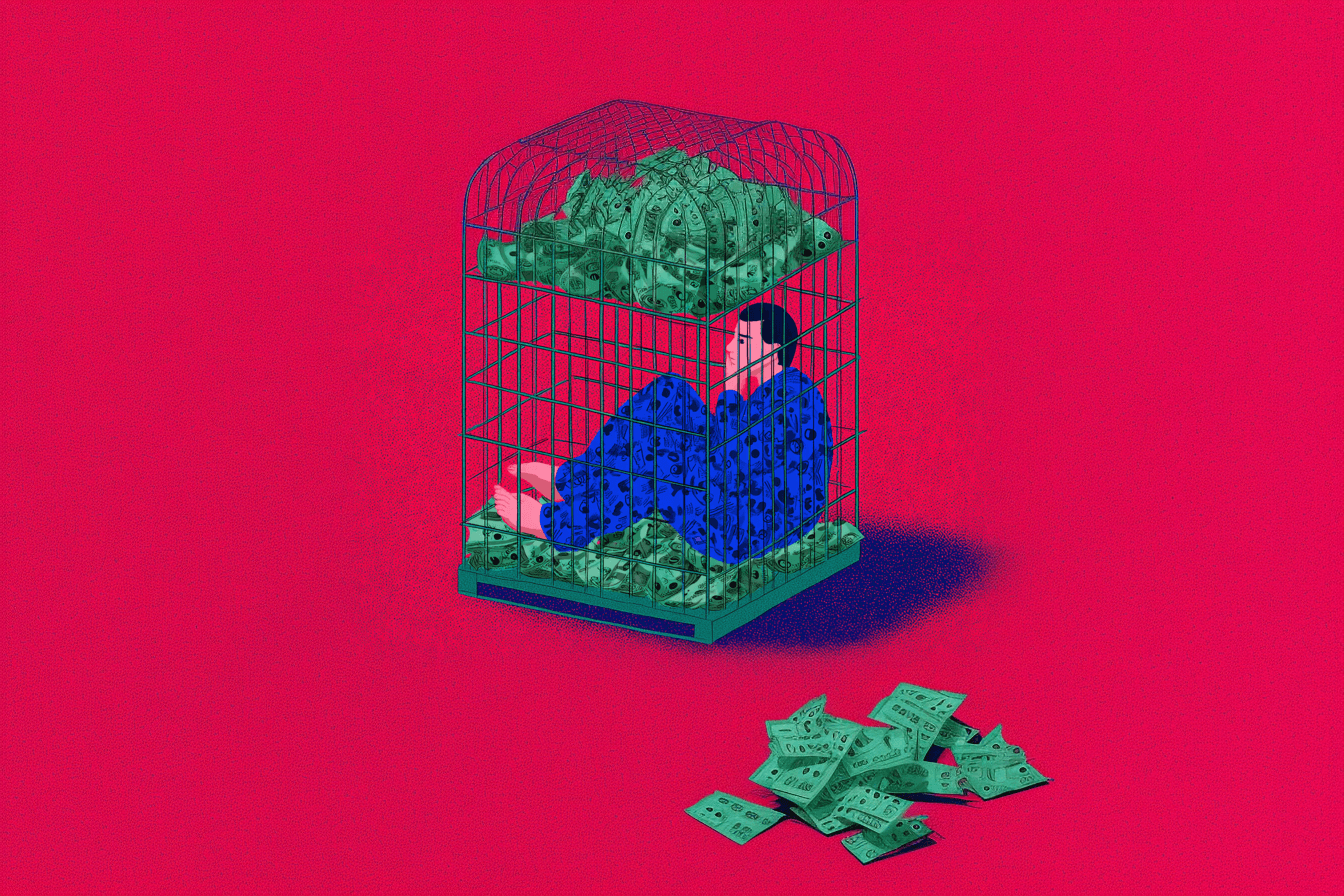

Cash became king. Physical dollars circulated hand to hand. People were paid in envelopes. ATMs dispensed local currency that lost value by the week. Bank balances existed on paper but were trapped behind arbitrary withdrawal limits.

The pound collapsed. The dollar replaced it.

When the state recedes

The deeper rupture was not only monetary but institutional.

State electricity generation dwindled to as little as one or two hours per day in many areas. Public services deteriorated. Government salaries became symbolic. The presidency sat vacant for months at a time amid political deadlock. Parliament met, postponed, met again.

But Lebanon has long operated with parallel systems. Private generators filled the electricity gap, charging neighbourhood subscriptions. Water trucks supplied buildings. Private schools and universities carried on. Hospitals, many privately run, adjusted their pricing structures. Telecommunications limped forward through a mixture of improvisation and diaspora support.

Where the state receded, private networks expanded.

This is not resilience in the romantic sense. It is adaptation born of necessity.

The diaspora economy

Remittances from abroad became lifelines. Lebanese communities in the Gulf, Europe, West Africa and the Americas sent dollars home. Families survived on transfers from children and siblings who had emigrated years earlier. New waves of young professionals departed, accelerating a brain drain that had long defined the country.

In effect, the Lebanese economy externalised itself.

The currency inside the country collapsed, but the currency outside — in foreign bank accounts and remittance channels — continued to function. The diaspora did not solve the crisis; it softened its edges.

It also deepened inequality. Those with access to fresh dollars navigated the crisis more smoothly than those dependent solely on local wages.

Why there was no implosion

The absence of a singular breaking point confounds outside observers. Why no revolution that resets the system entirely? Why no full-scale disorder?

Part of the answer lies in fragmentation. Lebanon’s political structure distributes power along sectarian lines, creating a system where no single actor can dominate — but also where responsibility diffuses easily. Anger exists, but it is often dispersed across competing narratives.

Part of the answer lies in exhaustion. After decades of civil war, regional conflict and intermittent instability, crisis has become ambient. The threshold for shock is high.

And part of it lies in pragmatism. When survival requires improvisation, ideology loses urgency. People queue at multiple ATMs. They convert pounds to dollars to fuel to cash again. They maintain two or three pricing systems in their heads. They calculate daily.

The extraordinary becomes routine.

The illusion of normalcy

Walk through Beirut’s central districts and you could mistake the scene for normalcy. Restaurants are full on weekends. New bars open. Imported goods appear in shop windows. Construction cranes dot parts of the skyline.

But this surface activity masks contraction.

The middle class has shrunk. Many professionals now hold two jobs. Public sector employees strike intermittently. Infrastructure remains brittle. Poverty has risen sharply. International institutions continue to warn of prolonged stagnation absent structural reform.

Normality, in this context, is curated. It exists in pockets sustained by remittances, cash dollars and a private sector operating beyond the state’s fiscal collapse.

It is both real and precarious.

Living with monetary memory

Perhaps the most profound change is psychological.

Currencies are collective memory devices. They encode trust in the future. When a currency disintegrates, it erodes not only purchasing power but belief in continuity.

In Lebanon, pricing something in pounds now feels temporary. Salaries are negotiated in dollars where possible. Contracts include hedging language. Businesses think in weeks, not years. Savings, if they exist, are kept in hard currency or outside the country.

The horizon shortens.

And yet life decisions continue. Couples marry. Entrepreneurs open cafés. Families send children to university. The future is not abandoned; it is recalibrated.

Infinite, not terminal

International observers often frame Lebanon’s crisis as a pending climax — a moment when the system must either collapse completely or be rebuilt.

But Lebanon operates differently. The crisis has become infinite rather than terminal. It stretches, absorbs, mutates. Political stalemates drag on. Reform negotiations stall. International assistance arrives in tranches, conditioned and delayed.

The country does not implode; it endures.

This endurance should not be mistaken for stability. A 98 per cent currency collapse is not survivable without cost. It hollowed out institutions, accelerated emigration and entrenched inequality. It shifted the burden of survival from the state to the individual.

Yet daily life persists.

Not because the crisis resolved, but because adaptation became a national skill.

Lebanon’s infinite crisis is not a singular event. It is a condition — one in which collapse and continuity coexist, and where the extraordinary is absorbed into the ordinary until it no longer registers as shock.

In other countries, historians will mark a year and call it the end of an era.

In Lebanon, the calendar simply turned.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.