The Greenland Question Nobody’s Asking the Greenlanders: 56,000 people caught between Danish sovereignty, American ambition, and Chinese mining interests. What do they actually want?

Writer Wills Mayani

Greenland is discussed in Washington, Copenhagen and Beijing as a strategic prize. But beneath the Arctic rhetoric lies a quieter question: how does a nation of 56,000 build independence without becoming someone else’s asset?

A territory that is always described as large

In the language of geopolitics, Greenland is never described as small.

It is the world’s largest island. It commands Arctic shipping routes. It holds rare earth minerals. It hosts a U.S. military installation. It sits between North America and Europe like a strategic hinge. It appears in defence briefings and resource forecasts, in NATO strategy documents and Chinese mineral analyses.

What Greenland rarely is, in those conversations, is human.

The island has roughly 56,000 people. Fewer than many European towns. Fewer than a single London postcode. Yet the way Greenland is discussed abroad, you would think it were an empty chessboard: Denmark on one square, the United States on another, China hovering at the edge.

But Greenland is not empty. It has a parliament in Nuuk. It holds elections. It debates mining policy, fisheries quotas, education funding and infrastructure. It argues about independence not as a slogan but as a budgetary calculation. It worries about housing shortages and youth migration. It carries a history that predates every foreign interest now circling it.

The question that dominates foreign headlines — who will control Greenland? — is not the one Greenlanders are asking.

Their question is quieter and more difficult: how do we become fully sovereign without becoming someone else’s asset?

A colony that is no longer called one

Formally, Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is an autonomous constituent country within the Danish realm, alongside the Faroe Islands.

The island was a Danish colony for centuries. In 1953, it was incorporated into Denmark’s constitution. In 1979, Home Rule granted it internal self-government. In 2009, after a referendum, the Self-Government Act expanded that autonomy dramatically. Greenlandic became the official language. Control over courts, policing and natural resources shifted to Nuuk. Denmark retained foreign affairs, defence and monetary policy.

The 2009 act also did something profound: it recognised Greenlanders as a people under international law with the right to self-determination. Independence is not a rebellion. It is a legal possibility, should Greenland choose it.

This matters. The future of Greenland is not a matter of external conquest or negotiation between foreign capitals. It is, constitutionally, a matter of Greenlandic consent.

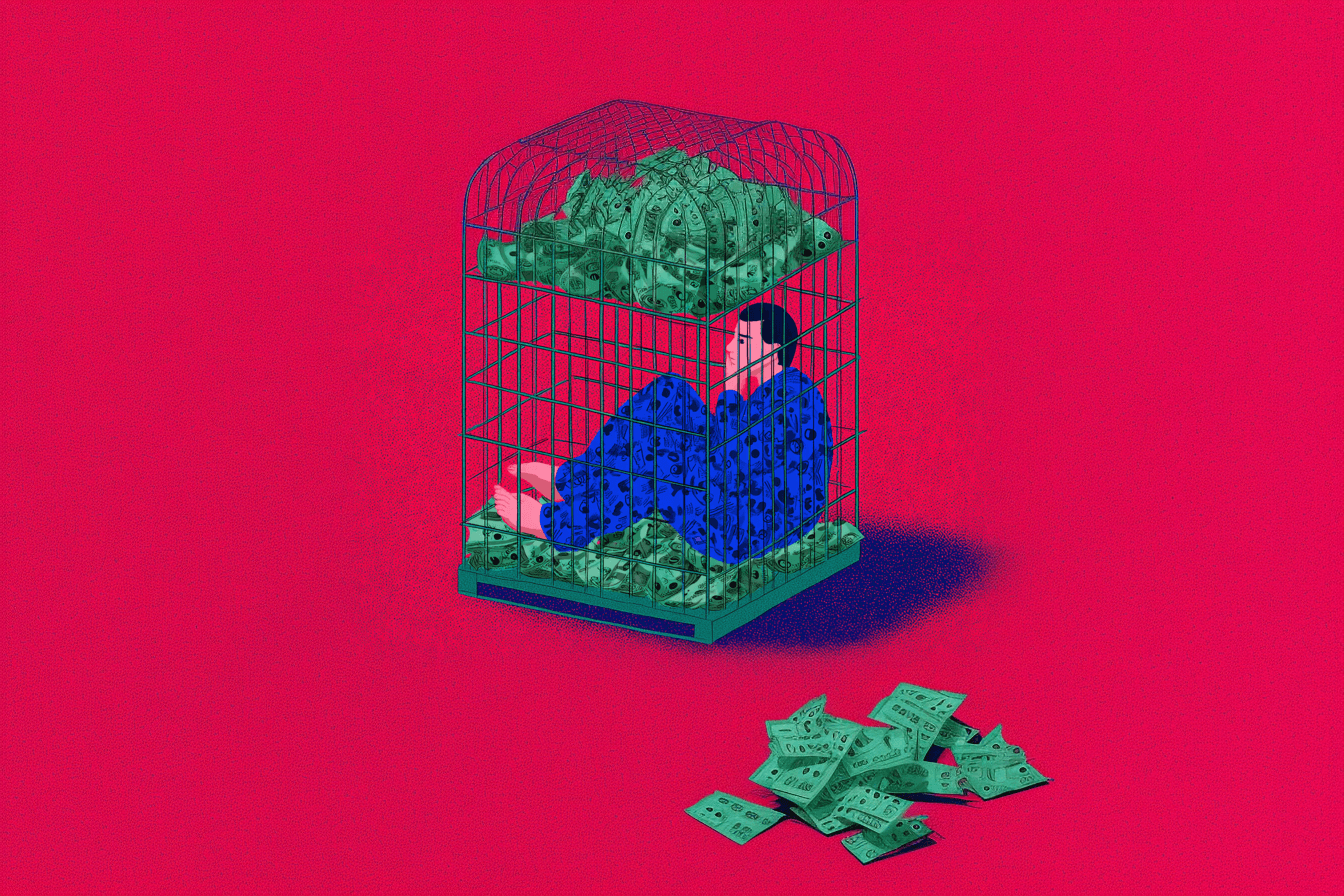

And yet consent is only meaningful when it is economically viable.

The number that shapes everything

Each year, Denmark provides Greenland with a block grant of roughly 3.9 billion Danish kroner — just over half a billion euros. It constitutes a substantial share of Greenland’s public budget.

Remove it abruptly and living standards would fall. Healthcare, education and public services would be strained. Independence, in theory, is straightforward. Independence, in practice, is arithmetic.

Polls have consistently shown strong support for eventual sovereignty. But that support is conditional. Greenlanders do not want independence that makes them poorer. They want independence that preserves dignity without sacrificing stability.

Greenland’s economy is narrow. Fisheries account for around 90 percent of exports. Shrimp and halibut underpin livelihoods across coastal communities. Climate change is opening new shipping routes and exposing mineral deposits, but it is also destabilising infrastructure built on permafrost and altering fishing patterns that have sustained towns for generations.

When foreign analysts talk about Greenland’s rare earth potential, they are speaking in strategic abstractions. When Greenlanders talk about the future, they are speaking about salaries, food prices and whether young people will stay or leave.

The difference is not rhetorical. It is existential.

The American fixation

In 2019, then U.S. President Donald Trump publicly floated the idea of purchasing Greenland.

The global reaction oscillated between amusement and disbelief. In Greenland, the reaction was sharper. The island’s leadership responded plainly: Greenland is not for sale.

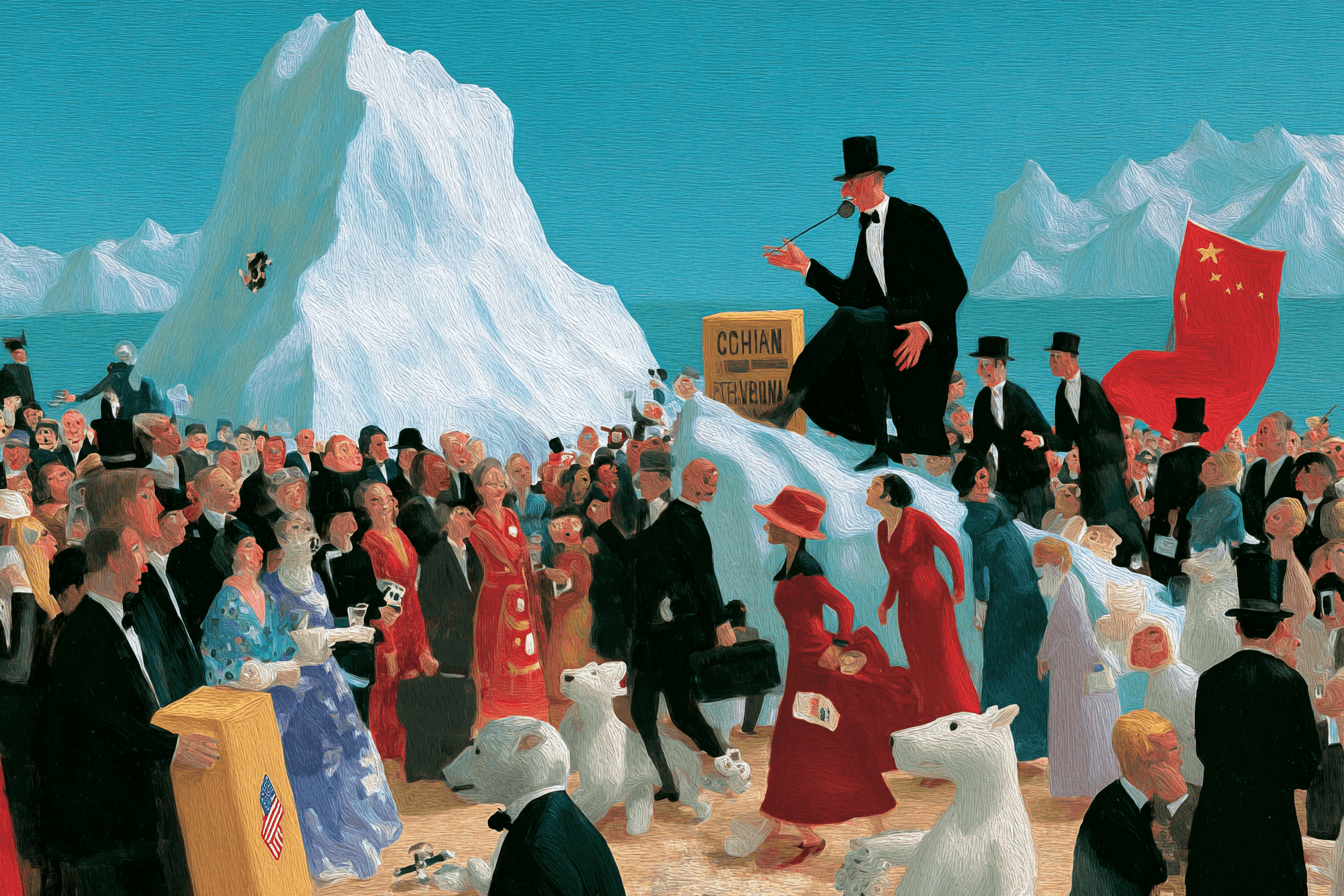

The United States already maintains a military presence at Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base) in the northwest. The base plays a role in missile warning and Arctic surveillance. Washington’s strategic interest is neither new nor frivolous. As Russia expands Arctic capabilities and China declares itself a “near-Arctic state,” Greenland’s geography matters.

But strategic interest is not sovereignty.

Surveys show overwhelming opposition among Greenlanders to becoming part of the United States. Even those frustrated with Denmark do not view annexation as liberation. Greenlandic nationalism is not a pivot toward another flag. It is a desire for their own.

The American debate frames Greenland as a security asset. The Greenlandic debate frames sovereignty as a responsibility.

They are speaking about different futures.

The Chinese shadow

China’s involvement has largely taken the form of economic interest — mining projects, infrastructure bids, rare earth exploration. Beijing does not need territorial control to benefit from Greenland’s resources. It needs contracts.

The Kvanefjeld rare earth and uranium project in southern Greenland became a flashpoint. It promised jobs and revenue. It also raised environmental concerns and political divisions. In 2021, Greenland’s election turned heavily on mining policy. A party opposed to uranium extraction won, and the project was halted.

This decision was not imposed by Copenhagen or pressured by Washington. It was made in Nuuk.

Greenlanders themselves weighed the promise of mineral revenue against environmental and social risk. The outcome demonstrated something often ignored in geopolitical commentary: Greenland is capable of exercising agency.

Mining remains controversial. It could reduce reliance on Danish subsidies. It could also bind the economy to volatile global markets and environmentally damaging industries. The choice is not ideological. It is practical.

The myth of emptiness

From a distance, Greenland appears vast and unoccupied — ice sheet, fjords, frontier. But it is not an extraction zone with a population problem. It is a society managing an unforgiving geography.

Communities are dispersed. There are few roads connecting settlements. Infrastructure is costly. Food and fuel are expensive. Climate change is both opportunity and threat: new maritime routes, new resource exposure, but also melting ice undermining buildings and coastlines.

The Arctic is often described as the next great economic theatre. For Greenlanders, it is home.

That distinction changes everything.

Independence as sequence, not slogan

Greenland’s independence movement is not theatrical. It is incremental.

The Self-Government Act provides a pathway. A referendum could be held. Negotiations with Denmark would follow. Issues of currency, defence, debt and international recognition would need resolution. Denmark has formally accepted that Greenland can choose to leave.

But independence requires replacement revenue. Fisheries alone are insufficient. Mining is uncertain. Tourism is growing but seasonal. The calculation is ongoing.

Greenland’s leaders often speak less about ideology and more about preparation. Build economic resilience first. Diversify. Strengthen administrative capacity. Then consider the final step.

Independence, in this framing, is not an emotional rupture. It is a staged transition.

The question nobody asks them

There is a smooth, exportable narrative available to outsiders. Denmark’s influence wanes. The United States circles. China invests. The Arctic becomes the new frontier.

It is tidy. It fits into panel discussions and defence white papers. It reduces Greenland to a square on a map.

But in Nuuk, the conversation sounds different.

It sounds like debates over fisheries management and mineral licensing. It sounds like arguments about how to keep young Greenlanders from relocating permanently to Copenhagen. It sounds like concern over whether an economy built on one dominant export can ever support full sovereignty without new pillars beneath it.

The island is not waiting to be claimed. It is calibrating its future.

What Greenlanders want is neither Danish paternalism nor American ownership nor Chinese leverage. They want the capacity to choose — genuinely choose — without the choice collapsing under financial strain. They want independence that feels earned rather than symbolic. They want the freedom to negotiate with larger powers without being absorbed by them.

For a country of 56,000, that is an extraordinary balancing act.

Greenland is not a prize. It is a polity navigating asymmetry in full view of the world’s largest powers. Its future will not be determined by a press conference in Washington or a mineral bid from Beijing. It will be determined in Nuuk — in referendums not yet scheduled, in budgets still being drafted, in elections where the central question is not who wants Greenland, but whether Greenland is ready.

The real Greenland question is not about ownership.

It is about timing.

And only Greenlanders can answer it.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.