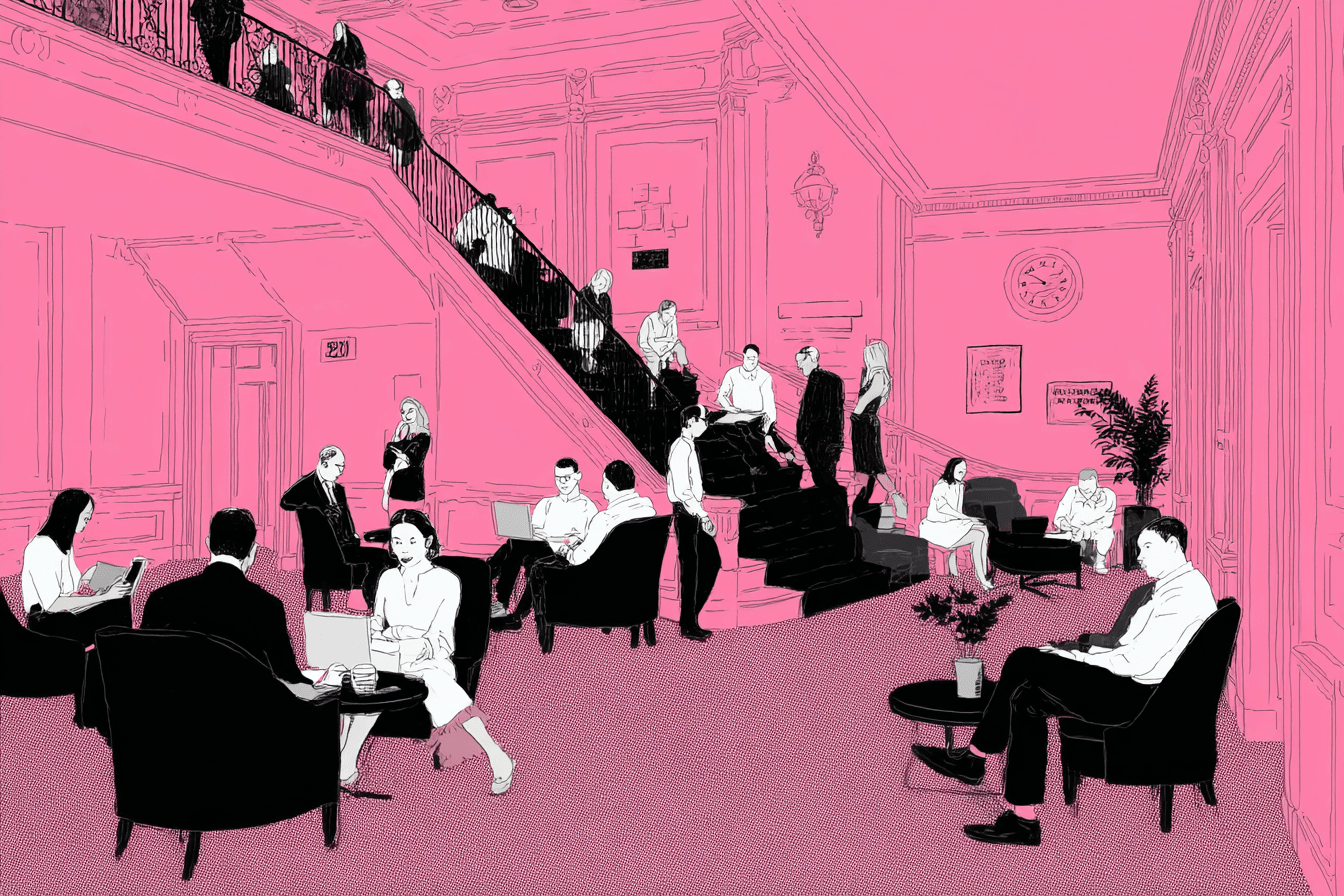

The Hotel Lobby as Co-Working Space: Ace, Hoxton and CitizenM figured it out first. Now every hotel is redesigning its ground floor for people who never check in.

Writer Wills Mayani

From Amsterdam to Shoreditch to SoHo, the hotel lobby has quietly become the most valuable square footage in the building — monetising remote workers, freelancers and locals who never book a room.

The Hotel Lobby as Co-Working Space

Ace, Hoxton and CitizenM figured it out first. Now every hotel is redesigning its ground floor for people who never check in.

At 9:47am on a Tuesday in Shoreditch, every long table in the Hoxton lobby is occupied. A founder is rehearsing a pitch. Two architecture students are editing a portfolio. A woman in a navy overcoat has been on the same Zoom call for 40 minutes, headphones pressed in, coffee untouched. Reception is quiet. The elevators glide up and down without ceremony. The real action is horizontal.

What you are looking at is not accidental.

It is not simply “vibes.”

It is a reallocation of capital.

Over the last fifteen years, and especially since 2020, the hotel lobby has been transformed from transitional dead space into revenue-generating, brand-defining, socially programmable infrastructure. The room once designed for waiting is now designed for staying. And often, staying without sleeping.

The historical mistake: measuring lobbies like corridors

For decades, hotel economics revolved around one dominant metric: RevPAR — revenue per available room. The business model was elegantly simple. Build rooms. Fill rooms. Optimise occupancy. The lobby was necessary but subordinate: a holding area, an intake valve.

Architects treated it as flow management. Finance teams treated it as overhead.

This was the first mistake.

The second mistake was psychological. The lobby was understood as administrative. Check in. Check out. Move on.

What brands like Ace and CitizenM realised in the late 2000s is that the lobby was not a corridor. It was theatre. It was symbolic space. It was, to borrow from sociologist Ray Oldenburg, a potential “third place” — neither home nor office, but civic ground.

Rory Sutherland’s work in behavioural economics provides a useful lens here. Sutherland often argues that businesses undervalue the intangible because it is hard to quantify. His famous example of the hotel doorman illustrates this beautifully: consultants remove him in the name of efficiency, only to erase ritual, warmth and perceived value in the process.

The lobby suffered a similar fate. It was seen as expensive real estate that did not directly produce room revenue. And so it was minimised, standardised, stripped of character.

Until a few brands did the opposite.

CitizenM and the inversion of square footage

When CitizenM opened its first hotel at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport in 2008, it committed a quiet act of inversion. The guest rooms were compact, around 14 square metres. Beds were pushed against panoramic windows. Storage was minimal. Efficiency ruled upstairs.

Downstairs, however, the square footage expanded.

Instead of a formal reception desk, CitizenM installed self-check-in kiosks. Instead of a transactional foyer, it created what it explicitly called a “living room”: Vitra chairs, curated art installations, communal tables, deep sofas, 24-hour bar service, and walls lined with books.

The spatial message was unmistakable: the most important room in the building was public.

CitizenM now operates in more than 30 cities globally, from London to New York to Kuala Lumpur. Its model has proven financially durable. Smaller rooms reduce construction and operational costs. Larger communal areas drive food and beverage revenue while building brand identity.

The lobby became the product.

Moxy, Hoxton and the industrialisation of atmosphere

Marriott’s Moxy brand adopted the model at scale. Rooms are intentionally compact — often between 150 and 200 square feet — freeing budget and spatial allocation for expansive, hybrid ground floors. Moxy executives have described their target consumer as someone who wants to “feel part of the community.” That language is strategic. Community creates dwell time. Dwell time creates spend.

Architectural analysis has pointed out the deliberate shift: less square footage for sleeping, more for gathering. In some properties, the bar is the check-in desk. In others, check-in happens on handheld devices while guests stand inside a social scene already in motion.

The Hoxton refined this into something more understated. Particularly in London and New York, its lobbies feel like neighbourhood living rooms rather than commercial coworking floors. The distinction is subtle but powerful. The atmosphere is permissive without being branded as “workspace.” That ambiguity reduces friction.

People do not feel like customers. They feel like participants.

Remote work and the monetisation of presence

The pandemic did not invent the lobby shift, but it accelerated it dramatically.

By 2023, global surveys indicated that hybrid work was firmly embedded across major urban economies. In the UK, Office for National Statistics data showed that roughly 40% of working adults were operating in some form of hybrid arrangement. In the United States, Pew Research found similar numbers among white-collar workers. The daily commute fractured.

Remote workers began seeking environments that were neither domestic nor corporate. Cafés were crowded. Traditional coworking operators faced turbulence — WeWork’s well-publicised collapse underscored the fragility of pure-play coworking economics.

Hotels were uniquely positioned to absorb the demand.

Unlike offices, they are designed for hospitality. Unlike cafés, they are designed for lingering. Unlike coworking chains, they already possess food and beverage infrastructure, staff and flexible seating.

Industry reporting by 2024 and 2025 consistently noted rising numbers of non-guests using hotel lobbies as workspaces. Some properties responded informally — embracing the traffic. Others formalised it. Accor partnered with Wojo to offer structured coworking access across hundreds of hotels in Europe. Several properties began selling day passes or monthly memberships.

The metric quietly evolved. It was no longer only RevPAR. It became revenue per available square metre.

The ground floor was no longer dead weight. It was programmable yield.

London: the return of the third place

In London, the hotel lobby’s transformation is inseparable from broader urban economics. Commercial rents remain high. Independent coworking operators struggle with lease obligations. Cafés operate on thin margins and high turnover.

The hotel lobby occupies a loophole in this equation. It is cross-subsidised by overnight revenue. It can afford to tolerate long dwell times. Its margins are diversified.

This makes it an ideal third place.

Oldenburg argued that third places are essential for civic health — informal spaces where social hierarchies flatten and conversation flows. In modern cities, many of those spaces have eroded. Pubs close. Independent bookstores shrink. Public libraries face funding cuts.

The hotel lobby has quietly filled that vacuum.

It is privately owned, but socially porous.

New York and the civic salon

Ace Hotel New York is often cited as an early exemplar. Its lobby became a magnet for creative workers long before “digital nomad” became cliché. The design was intentional: oversized communal tables, accessible power outlets, lighting warm enough to flatter but bright enough to work.

The hotel did not aggressively police non-guests. It absorbed them. The presence of freelancers and entrepreneurs amplified brand value. The hotel became culturally embedded.

In behavioural terms, this created signalling effects. Working at Ace signalled belonging to a certain creative class. The hotel accrued intangible prestige. That prestige translated into higher room desirability.

The lobby, in other words, became marketing.

Paris and the aesthetic arms race

In Paris, where café culture is deeply entrenched, hotels faced a different challenge. They could not merely replicate coworking tables. They had to compete aesthetically.

CitizenM properties near La Défense and République, as well as boutique lifestyle hotels in the Marais, leaned into curated art, residential lighting and layered interiors. The goal was not overt coworking functionality but atmospheric permanence.

Paris demonstrates a crucial point: the lobby shift is not simply functional. It is cultural. Each city filters the model through its own design language and social habits.

The behavioural thesis

Why does this work so effectively?

First, liminality. The lobby sits between public and private space. It feels accessible but secure. This ambiguity reduces social anxiety.

Second, optionality. In an office, productivity is mandatory. In a café, turnover is implied. In a hotel lobby, both are optional. You can work. You can linger. You can simply exist.

Third, theatre and signalling. Hotels are inherently performative environments. Lighting, scent, materiality — all calibrated. People enjoy working inside curated environments. It feels elevated.

Sutherland’s broader thesis is that humans value emotional and symbolic benefits disproportionately to measurable utility. The hotel lobby, once viewed as inefficient, is now understood as experiential capital.

Tensions and limits

The model is not frictionless.

Security concerns require balance. Too open, and the space risks feeling uncontrolled. Too restrictive, and the cultural energy dissipates.

There is also class tension. A £5 coffee can function as soft gatekeeping. Hotels must decide whether they are neighbourhood commons or premium enclaves.

Some properties formalise access via memberships. Others rely on social signalling to self-regulate.

The tension is structural: hotels are private enterprises occupying increasingly public roles.

The macro shift: hotelification of the office

While hotels absorb remote workers, offices are moving in the opposite direction.

The term “hotelification of the office” has entered workspace design discourse. Corporations are redesigning headquarters to mimic hospitality: lounge seating, coffee bars, concierge-style reception, flexible zones.

Both typologies are converging toward a middle ground defined by comfort, flexibility and experience.

The boundary between hospitality and workplace is dissolving.

The strategic conclusion

The hotel lobby was once measured as cost per square foot.

It is now measured as brand amplifier, revenue generator and cultural anchor.

CitizenM inverted the model in 2008. Ace and Hoxton refined it. Moxy scaled it. Accor institutionalised it.

The most valuable room in the hotel is increasingly the one no one sleeps in.

And the people fuelling its profitability may never check in.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.