The Netflix Effect: How streaming killed cinematic risk

Writer Wills Mayani

Budgets keep climbing, yet the work feels flatter: safer scripts, noisier spectacle, rushed finishing and fewer films that genuinely divide opinion. Streaming didn’t kill cinema outright. It rewired what movies are for.

The new deal: comfort, not conviction

There is a particular kind of modern movie that feels designed to be consumed rather than encountered. It arrives on a Friday, it is watched in fragments across a weekend, it earns polite praise for being “fun” or “easy”, and by Tuesday it has already begun to dissolve. No one hated it enough to argue about it. No one loved it enough to quote it. It did its job: it filled the home screen, held attention for long enough, and stopped the subscriber from wandering.

This is the quiet trade at the heart of streaming. The pitch was liberation—more choice, more global reach, fewer gatekeepers—yet the mature outcome resembles something closer to managed comfort. Not because executives hate art, or because audiences have suddenly lost taste, but because the business logic has changed the question that films are built to answer. Cinema once asked: will people leave home for this? Streaming asks: will people stay?

That shift sounds modest. It isn’t. It changes how stories are shaped, how budgets are justified, how scripts are rewritten, how scenes are cut, how images are finished, and how risk is priced.

The subscription lens: watch-time beats impact

Box office was a brutal but clarifying metric. A theatrical film either pulled people through a doorway or it didn’t, and failure was public. Studios could still make bad decisions—Hollywood has always loved a mirage—but the marketplace imposed a kind of accountability. A movie had to convince you before it had you.

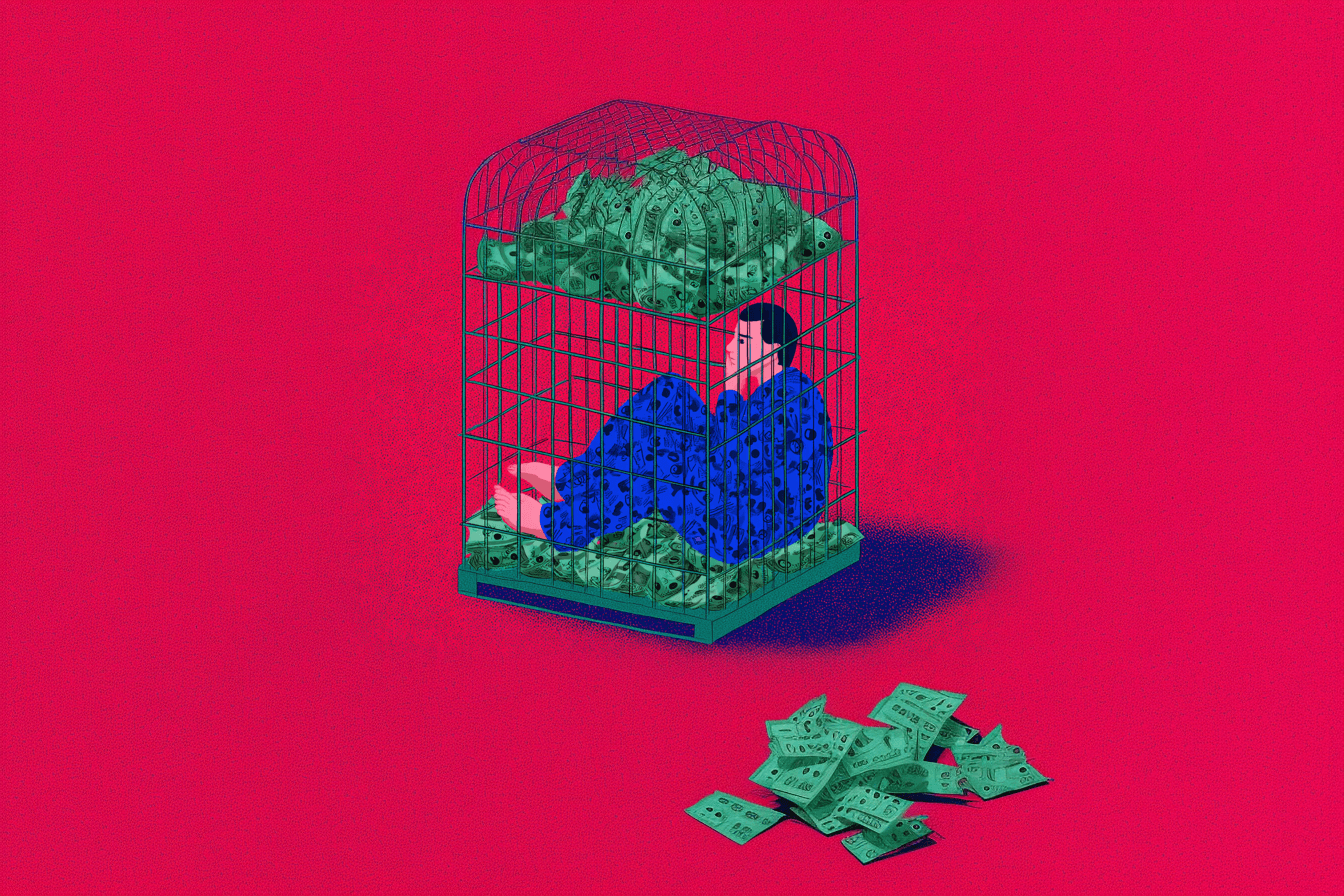

Streaming reverses the order. The platform already has you. The “sale” has been made in advance, and the film is now part of a retention machine whose key variables are different: frequency of use, breadth of appeal, completion rates, and the ongoing habit of opening the app. A film becomes a unit of engagement, competing not only with other films but with series, documentaries, comfort rewatches, and the infinite scroll of the catalogue.

This is why the industry has begun to speak less about attendance and more about hours. In Netflix’s own engagement reporting, viewing is framed in terms of time watched and “views” derived from hours watched divided by runtime. The language itself implies the new value system: the job is to accumulate watch-time, not to create a moment that culture cannot ignore.

When you optimise for watch-time, you optimise for frictionless viewing. You avoid sharp tonal shifts. You sand down ambiguity. You keep the plot legible even if a phone is in the viewer’s hand. You front-load clarity, repeat key information, and reduce the number of sequences that demand full attention. You write not for the darkened room but for the distracted lounge.

The result is not always bad. It is often competent. But competence is not what people mean when they mourn cinematic risk.

Why budgets grew while the work shrank

The strangest part of the modern landscape is not that studios play safe. They always have. It is that safety now arrives with astonishing price tags. The industry is spending more, in more places, on more content—Netflix alone has signalled content cash spending on the order of tens of billions annually—yet the viewer’s complaint is increasingly consistent: the dialogue feels thinner, the images feel less finished, the spectacle feels noisier but less memorable.

How can a film look cheaper when it costs more?

Part of the answer is that “budget” is no longer a clean indicator of time. It can represent scale without representing breathing room. You can spend lavishly and still rush, because the schedule is compressed, the release date is fixed, and the platform has already mapped the quarter’s slate. In an ecosystem built on steady replenishment, the pipeline matters as much as the product. Quantity is not a side effect; it is the strategy.

This is where the paradox becomes visible on screen. When timelines tighten, finishing suffers first—because finishing is the part of filmmaking that quietly requires patience.

VFX, post, and the cost of speed

There is a myth that modern films look artificial because audiences have become snobs. The less glamorous truth is that a great deal of the work is simply being done under pressure. Over the past decade, the visual effects industry has faced persistent labour stress, deadline compression and a volume problem—more shots, more versions, more deliverables, delivered faster. Analysts and industry observers have been documenting this strain for years, and the streaming boom has intensified the demand for feature-level spectacle across episodic and feature formats alike.

When production runs late—and many productions now run late—post-production is asked to absorb chaos. This isn’t just an aesthetic problem; it’s structural. Research into post-production culture repeatedly points to late decision-making, limited transparency, and the cascading consequences of schedule compression. The phrase “we’ll fix it in post” used to be an indulgence. In the streaming era it can become a business plan.

The visible symptom is the contemporary blockbuster look: images that are technically dense yet oddly weightless; action that feels like previsualisation made literal; colour grading that flattens texture into a uniform sheen. It is not that artists have forgotten how to do great work. It is that great work is harder to do at industrial speed, especially when last-minute changes ripple through hundreds of shots.

The irony is sharp. The era of supposedly infinite budgets can also be the era of least time.

The death of the middle, and why risk lived there

If you want to understand why cinematic risk feels rarer, you have to look beyond Netflix originals and into the shape of the overall market. A healthy film ecosystem used to have a thick middle: the mid-budget drama, the adult thriller, the strange comedy with a star who wanted to try something, the film that didn’t need a billion-dollar gross to be considered a success.

That middle has been thinning for years. Some of it is pandemic shock. Some of it is the rising cost of marketing theatrical releases. Some of it is a cultural migration towards home viewing. But research on industry “product composition” suggests that streaming competition has been associated with fewer medium-budget movies, even as the low-end and the tentpole extremes persist. The market becomes polarised: cheap, niche projects at one end; enormous spectacle at the other; fewer films in the zone where writers, directors and studios historically took risks that were survivable.

And risk is easiest to take when failure is not fatal.

In the box-office era, a studio could back a handful of mid-budget swings because the economics allowed it. In the streaming era, the incentives skew toward either (a) low-cost volume that pads the library, or (b) enormous “event” bets that can be marketed as essential. The in-between—the place where interesting, culturally resonant cinema tends to live—gets squeezed.

Dialogue got worse because the room changed

It is tempting to blame dialogue on talent. It is more accurate to blame it on environment.

Dialogue thrives when scenes are allowed to breathe: when characters are permitted to avoid the obvious line, when tension can sit in silence, when information can be implied rather than announced. That kind of writing assumes attention. It assumes that a viewer is watching—properly watching.

Streaming has normalised a different relationship to attention. Many viewers watch while doing something else, and platforms have learned to treat that behaviour not as a problem but as a baseline. If the metric rewards completion and retention, then the writing adapts accordingly. Exposition becomes more explicit. Motivations are stated rather than suggested. Emotional beats are underlined. The script becomes legible at a glance.

This is not subtle censorship. It is optimisation.

You can hear it in the cadence of modern blockbuster speech: lines shaped for immediate comprehension rather than lasting resonance. You can see it in the structure: shorter scenes, more frequent reminders, fewer sequences that risk confusion. The craft shifts from poetry to customer service.

The global neutral: risk is local, algorithms are not

Streaming is global by default. That is one of its great achievements. But global reach creates its own pressure: a tendency toward cultural neutrality.

Local specificity can be commercially risky if it reduces cross-border comprehension. Humour doesn’t always translate. Social nuance can be misread. Idiom can flatten. The safer play is to write toward a kind of international middle: clear stakes, familiar genres, recognisable archetypes, dialogue that travels.

This is why some big streaming films feel as if they were designed in an airport lounge: competent, polished, broadly legible, and strangely locationless. Even when the setting is specific, the sensibility can be frictionless. The point is not to alienate; the point is to keep the widest possible set of viewers moving forward.

Risk, by contrast, is often stubbornly local. It insists on taste. It creates disagreement. It produces cults and critics. It can be awkward in translation—and that awkwardness is part of the art.

The cinema used to be a risk filter

The theatrical window did more than generate revenue. It performed a cultural function: it filtered what deserved collective attention.

When a film was released in cinemas, it submitted itself to the public ritual. People paid, travelled, sat in the dark, and had an experience that could not be paused. The film, in turn, had to earn that commitment. It had to be worthy of the room. That pressure produced a certain discipline.

Streaming removes the room. The film is now one tile among many, and the viewer can leave at any moment. That changes pacing. It changes editing. It changes how much friction a film can tolerate before the audience clicks away. A scene that would hold in a cinema may be trimmed at home. A slow build becomes a retention risk. The film is cut to survive the scroll.

There is a reason slow-burn storytelling is often described as endangered in the algorithmic era. It is not that audiences dislike patience. It is that platforms often cannot afford it.

The prestige mirage: more “cinematic”, less cinema

Streaming can still produce excellent films. It can still fund ambitious directors. It can still write cheques that traditional studios would not. The critique is not that everything on streaming is bad. The critique is that the system’s default incentives push against the very conditions that make cinema feel alive: time, risk, specificity, and the possibility of failure.

Even the “prestige” version of streaming cinema can carry a certain hollowness. A film may look expensive, feature stars, and launch with high visibility, yet still feel like it was built to be broadly approved rather than sharply felt. It is cinematic in surface grammar—wide shots, glossy production design, sweeping scores—without the deeper courage that cinema historically demanded: the willingness to lose part of the audience in order to reach the rest.

In older studio eras, the risk was taken in the work itself. Now the risk is often taken in the spend. A platform will wager $200 million on a recognisable premise rather than $30 million on a film that might divide opinion. The money gets braver while the storytelling gets safer.

What would reverse the Netflix Effect?

The streaming era is not going away. Nor should it. It has expanded access, globalised taste, and created a new kind of cultural circulation. But if the question is how to restore cinematic risk, the answer is not nostalgia. It is structure.

Risk returns when the industry rebuilds the middle: films that are big enough to matter, small enough to survive, and free enough to be strange. Risk returns when schedules allow finishing to be a craft rather than a sprint. Risk returns when platforms are willing to reward impact alongside engagement, and when they accept that a film can be culturally valuable even if it is not universally completed.

And risk returns when we treat attention as something worth earning again.

The Netflix Effect did not kill cinema with malice. It did it with logic. It replaced the old question—will you buy a ticket?—with a quieter one: will you keep watching? Over time, that question rewired the shape of movies. Not into worse art, necessarily, but into safer art. Art that slides by. Art that fills time.

The tragedy is not that streaming made films cheaper or smaller. It made them smoother. And smoothness, in cinema, is rarely where the thrill lives.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.