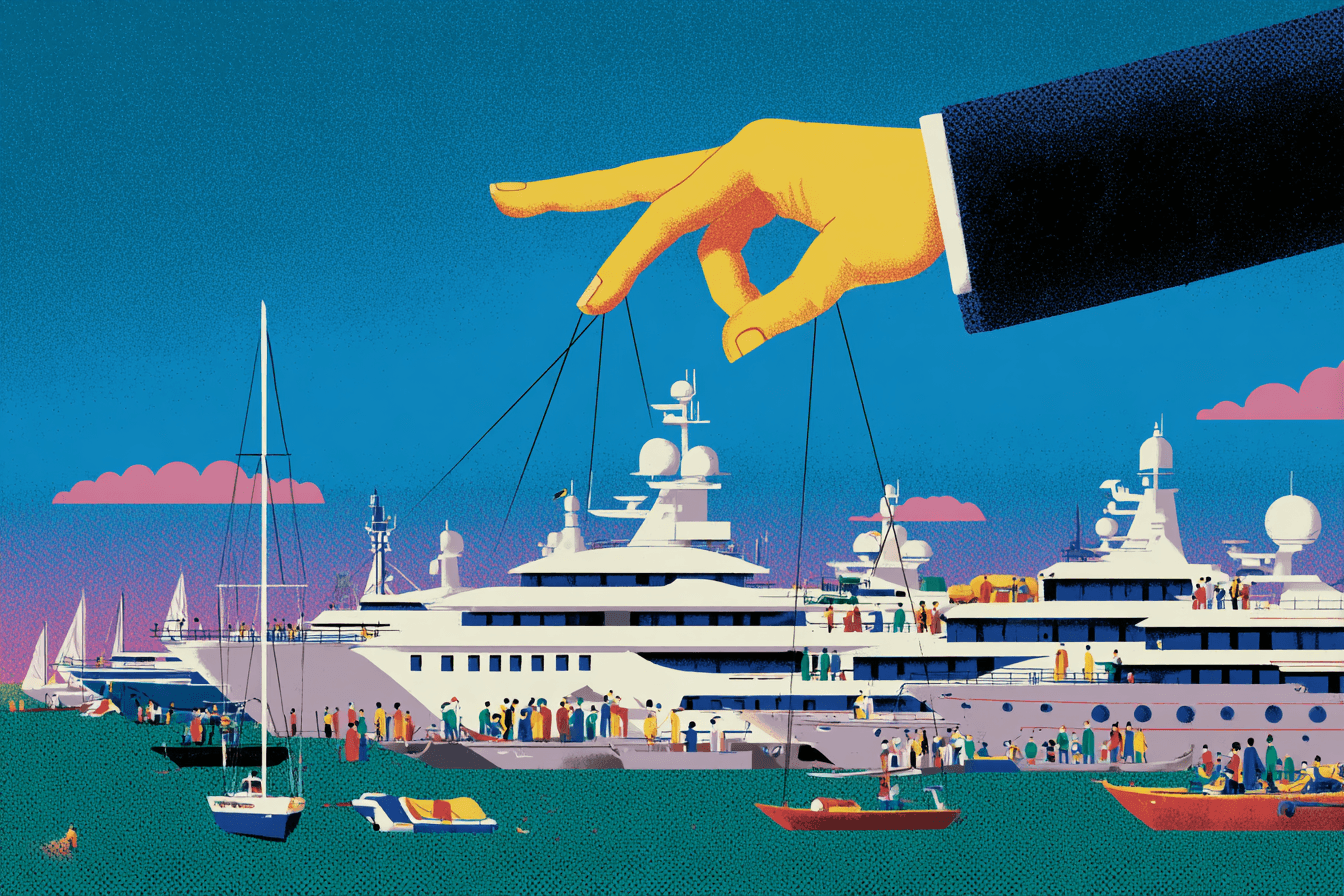

Who Owns the Mediterranean?: Superyacht marinas, private islands, and the quiet land grab reshaping Southern Europe's coastlines

Writer Wills Mayani

From sovereign wealth funds to Golden Visa investors, control of Mediterranean coastlines is shifting through balance sheets rather than flags. The sea remains open. Its most valuable edges do not.

A sea that belongs to everyone — and no one

The Mediterranean has always projected a sense of permanence. Civilisations rose and fell along its edges, empires claimed its waters, trade routes crossed its surface, yet the sea itself remained stubbornly indifferent to ownership. It connects Marseille to Naples, Dubrovnik to Mykonos, Barcelona to Beirut, as it has for millennia. Public ferries run their routes. Fishing vessels set out before dawn. Tourists crowd municipal beaches each summer. On paper, nothing fundamental has changed.

And yet something has.

The Mediterranean did not change hands through conquest or treaty. It was not seized in a dramatic geopolitical rupture. It has been acquired incrementally, through development concessions, investment vehicles, marina expansions, rezoning approvals, and property transfers. The process is legal, procedural and often presented as economic progress. Each individual decision appears rational in isolation. Collectively, they are transformative.

The sea remains common.

Its most valuable edges do not.

The marina economy

To understand the shift, begin with infrastructure.

Over the past two decades, the number of large superyachts operating globally has expanded dramatically. Vessels exceeding 40 metres have multiplied. Those exceeding 60 or 80 metres have become a status category of their own. These yachts require specialised berths, deep-water access, reinforced docking systems, and premium shore facilities.

Traditional Mediterranean harbours were not designed for this scale.

The result has been a wave of marina modernisation and expansion stretching from the Côte d’Azur to Montenegro. Ports in Antibes, Barcelona, Genoa, the Balearics and the Adriatic have undergone redevelopment to accommodate vessels that can exceed 100 metres in length. Berthing fees for such yachts can reach hundreds of thousands of euros per season. Annual contracts for prime locations become multi-million-euro revenue streams.

Marinas are not merely docks. They are asset classes.

In many cases, municipalities retain nominal ownership of the harbour while granting long-term concessions — often 30 to 50 years — to private operators. These operators invest capital to upgrade facilities and in return gain the right to manage berths, services and adjacent commercial development. The financial model is straightforward: maximise high-value berth occupancy, integrate retail and hospitality, and capture recurring service revenue.

Over time, harbour logic shifts.

A fishing fleet occupying lower-margin space becomes economically inefficient. A berth accommodating a 20-metre boat generates a fraction of the revenue of one holding an 80-metre yacht. The physical configuration of the port adjusts accordingly. Larger berths are prioritised. Shore power systems are upgraded. Security tightens. Access becomes curated.

The harbour remains technically public.

Its economic orientation is no longer neutral.

Private islands and portfolio assets

Beyond the marinas lie the islands.

Private island transactions in the Mediterranean have increased in visibility over the past two decades. Greek islands, in particular, saw a surge of interest during and after the sovereign debt crisis. Economic distress combined with liberalised investment rules created acquisition opportunities for foreign buyers seeking seclusion and prestige.

In Italy, France and Croatia, smaller islands and coastal estates have similarly changed hands through corporate structures rather than direct personal purchase. Often, these assets are held by limited liability companies registered in tax-efficient jurisdictions. Ownership becomes layered, sometimes opaque, embedded within global wealth management frameworks.

For buyers, the appeal is multifaceted: privacy, security, asset appreciation, and a hedge against geopolitical volatility. Mediterranean real estate offers lifestyle utility combined with capital preservation. In periods of global uncertainty, tangible coastal property retains symbolic and financial value.

But island ownership is rarely self-contained.

Development follows acquisition. Access roads are improved. Harbours are upgraded. Private airstrips are proposed. Utilities are extended. Environmental impact assessments become part of negotiation. The line between preservation and transformation blurs.

An island may appear untouched from offshore.

Its governance may be entirely restructured.

The Golden Visa era

Southern Europe’s post-2008 economic fragility accelerated the process.

In the wake of the global financial crisis and the Eurozone debt crisis, several Mediterranean countries introduced residency-by-investment programmes — widely known as Golden Visas. Portugal, Spain and Greece allowed non-EU nationals to secure residency rights through qualifying real estate purchases. Cyprus and Malta went further with citizenship-by-investment programmes before regulatory scrutiny tightened the landscape.

The policy rationale was explicit: attract foreign capital, stabilise property markets, and stimulate construction sectors battered by recession.

The results were measurable.

Billions of euros flowed into residential property in Lisbon, Athens, Barcelona and coastal resort regions. High-end developments marketed directly to international investors proliferated. Coastal towns that had suffered from economic contraction saw renewed building activity.

But capital does not distribute evenly.

Golden Visa investment tended to cluster in already desirable zones — historic centres, waterfront districts, premium coastal areas. In Athens, property values in central districts surged. In Lisbon, local housing affordability deteriorated sharply. In Spanish coastal cities, foreign ownership shares increased significantly in certain neighbourhoods.

Residency programmes were not designed to transfer political control. They were designed to stimulate economic recovery.

Yet by linking property ownership to mobility rights within the European Union, they redefined coastal real estate as a gateway asset. A villa overlooking the sea was not merely a second home. It was a mobility instrument, a residency strategy, a geopolitical hedge.

The Mediterranean coastline became embedded in global migration calculus.

Sovereign wealth and strategic capital

The Mediterranean is not only absorbing private wealth. It is absorbing state capital.

Over the past fifteen years, sovereign wealth funds — particularly from Gulf states — have steadily expanded their footprint across Southern Europe’s coastal real estate and hospitality sectors. These investments are rarely framed in geopolitical terms. They are described as long-term diversification strategies: acquiring stable, income-generating assets in politically secure jurisdictions with strong tourism fundamentals.

But scale matters.

Qatar Investment Authority has acquired landmark hotels on the French Riviera and stakes in luxury developments across Italy. Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala and other Emirati vehicles have participated in hospitality, infrastructure and mixed-use development projects throughout Spain and Southern France. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, while more publicly associated with sport and technology investments, has also expanded its global real estate exposure in high-end markets that include Mediterranean assets.

On paper, these are rational capital flows. Europe offers legal certainty. The euro offers currency stability. Mediterranean luxury real estate offers global brand value and scarcity.

But sovereign capital differs from private capital in one essential respect: it carries strategic patience. Unlike private equity funds operating on a seven-year cycle, sovereign wealth funds are not pressured by exit timelines. They can hold assets across decades, weather downturns, and influence redevelopment trajectories over long horizons.

This changes negotiation dynamics.

When a municipality in Spain or Italy considers rezoning coastal land for a marina expansion or hospitality complex backed by a sovereign investor, the economic calculus extends beyond simple tax revenue projections. It intersects with diplomatic relationships, employment promises, and national investment policy. Coastal redevelopment becomes part of a broader matrix of foreign direct investment flows.

It would be simplistic to frame this as a “takeover.” These are legal transactions within regulated markets. Yet when a growing share of high-value coastal infrastructure is controlled by foreign state capital — even indirectly through funds and holding structures — local decision-making environments subtly shift.

Power rarely announces itself.

It embeds itself in ownership structures.

The service economy beneath the yachts

Every superyacht berth generates an ecosystem.

Crew housing, maintenance contractors, provisioning suppliers, luxury retail, security services, transport operators — all benefit from high-end maritime activity. Mediterranean port towns have increasingly oriented their labour markets around servicing mobile wealth.

This creates employment. It also creates dependency.

Seasonal tourism has long shaped coastal economies, but superyacht concentration amplifies volatility. When global economic conditions tighten or geopolitical events alter sailing routes, ports experience sharp fluctuations in revenue. During the COVID-19 pandemic, yacht activity paused abruptly in certain basins before rebounding in others. Flexibility for capital often translates to precarity for labour.

Moreover, the wages generated by luxury service roles do not necessarily compensate for rising housing costs in coastal towns where real estate has appreciated rapidly due to international demand. Younger residents frequently relocate inland. Seasonal workers commute long distances. Local demographics age or stratify.

The sea remains open.

Participation in its most profitable segments becomes selective.

The climate paradox

The Mediterranean basin is warming faster than the global average. The region faces acute exposure to sea-level rise, coastal erosion, biodiversity loss and extreme heat events. Southern European governments have acknowledged the increasing vulnerability of coastal infrastructure to climate stress.

At the same time, high-end coastal development has intensified.

Marina expansions require dredging. Larger superyachts demand deeper berths and reinforced dock systems. Seawalls and protective structures alter natural shoreline dynamics. Luxury real estate complexes increase water demand in regions already facing seasonal scarcity.

The contradiction is structural.

The economic engine driving much of this development — luxury maritime tourism and high-net-worth seasonal residency — depends on environmental stability and aesthetic preservation. The Mediterranean’s brand is built on its coastline. Yet the very infrastructure supporting this economic model increases ecological pressure.

Climate risk introduces a further asymmetry.

The superyacht owner can relocate. If summer conditions become untenable in one basin, vessels can shift to northern Europe, North America, or other seasonal circuits. High-net-worth property owners can diversify holdings geographically.

Local communities cannot.

When erosion affects a public beach, it is the municipality that finances remediation. When heatwaves stress water supply systems, it is residents who bear the cost of rationing. Insurance premiums for coastal properties rise; in some regions, insurers withdraw coverage entirely. Smaller-scale local operators — fishermen, independent guesthouses, family-run businesses — operate with thinner margins and less capacity to absorb climate volatility.

Ownership shapes resilience.

If the dominant capital in a region is mobile and diversified, while the population is rooted and exposed, risk distribution becomes uneven. Environmental externalities are socialised; financial gains are concentrated.

The paradox is not that development exists.

It is that climate vulnerability and capital consolidation are accelerating simultaneously.

Does ownership matter?

At first glance, the Mediterranean still feels accessible.

Public beaches remain legally protected in many countries. Ferries cross busy routes. Fishing vessels still operate in traditional waters. Coastal promenades are filled in the evening with families and tourists alike.

The sea has not been fenced.

Yet ownership matters because it defines who shapes long-term trajectory.

Consider marina concessions. When a municipality grants a 30- or 40-year concession to a private operator, the economic logic of that harbour shifts. Revenue maximisation becomes central. Berth allocation prioritises larger vessels with higher fee potential. Service ecosystems adjust accordingly. The local fishing fleet may not be expelled, but it may be marginalised.

Consider zoning decisions. When adjacent land is controlled by investment vehicles seeking integrated luxury development, lobbying for regulatory amendments becomes rational. Height restrictions, density limits, environmental assessments — these become negotiable variables within a development framework rather than fixed civic boundaries.

Consider property appreciation. When coastal real estate becomes a globally traded asset class, housing supply responds to international purchasing power rather than local income levels. Residents may retain formal access to their towns, but affordability constraints reshape demographics. Younger generations relocate inland. Seasonal occupancy increases. Communities become partially dormant in off-season months.

Ownership influences not only who profits, but who decides.

Who determines the balance between public space and private concession? Who weighs short-term economic stimulus against long-term ecological integrity? Who sets the price threshold for participating in coastal life?

These decisions are rarely dramatic. They unfold through planning committees, infrastructure tenders, and investment agreements. No single vote transfers “the Mediterranean” to a new owner.

Instead, incremental shifts accumulate.

The sea itself remains common.

Its most valuable nodes do not.

And over decades, control of nodes becomes control of narrative — what kind of coastline is built, who it is built for, and which version of Mediterranean identity endures.

Ownership does not need to exclude the public to matter.

It only needs to steer direction.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.