Why Menswear Is Suddenly Interesting Again: Phoebe Philo’s return, Loewe’s rise, quiet tailoring, anti-streetwear — men’s fashion is having its most creative moment in a decade

Writer Wills Mayani

After the streetwear decade, menswear is shifting from logos to language: cut, fabrication, restraint, and ideas. The money is moving too — and the creative director chairs suggest this isn’t a trend but a structural reset.

Why Menswear Is Suddenly Interesting Again

Phoebe Philo’s return, Loewe’s rise, quiet tailoring, anti-streetwear — men’s fashion is having its most creative moment in a decade

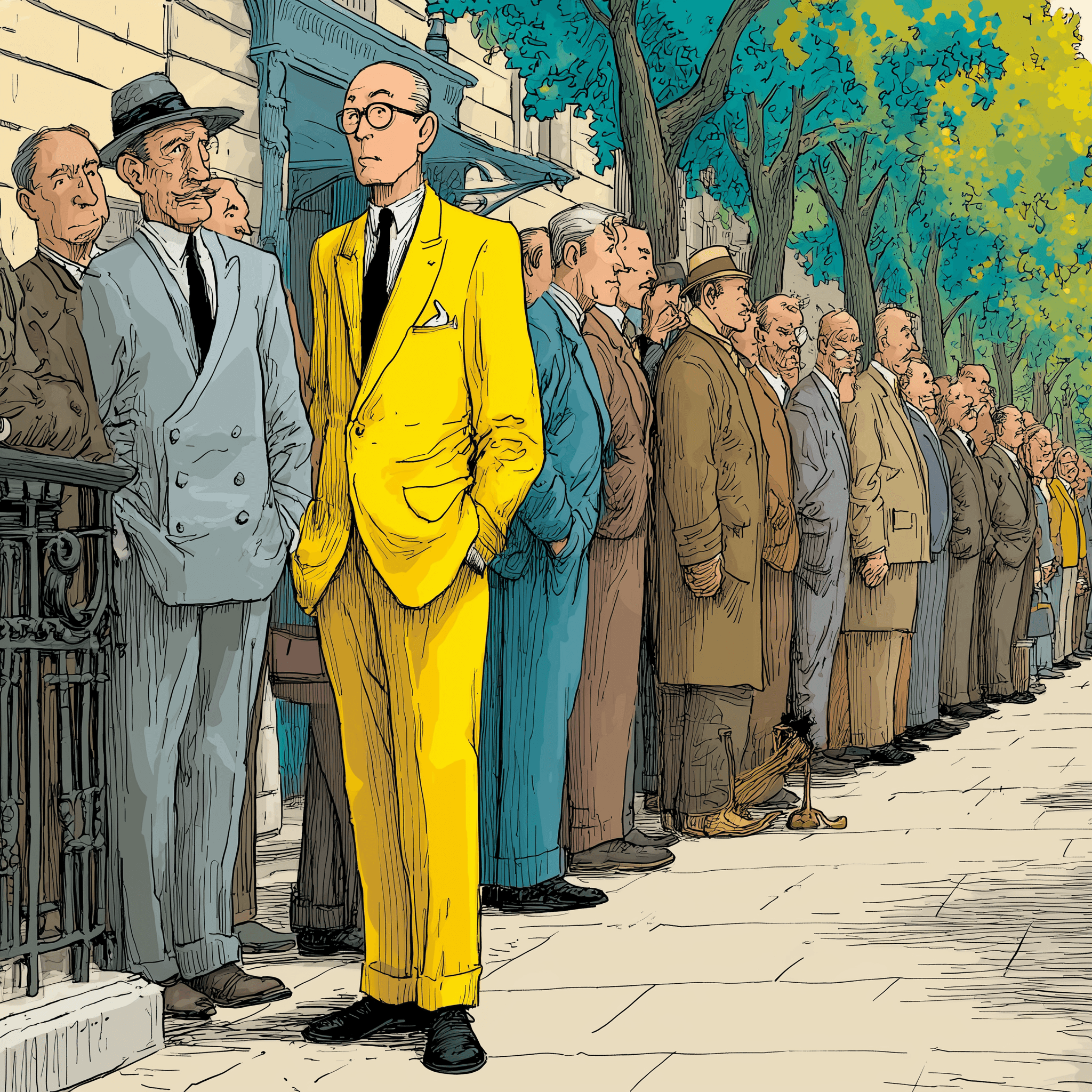

For most of the last decade, menswear was loud in the way a stadium is loud: not because it was saying something new, but because the volume was the point. Logos, collaborations, drops, queues, resale graphs that looked like stock charts. The industry learned to manufacture urgency and call it culture. If you wanted to understand what mattered, you didn’t look at a lapel or a sleeve head; you looked at a calendar.

Then, almost without announcement, menswear began to change. The noise didn’t disappear — fashion never truly returns to silence — but it stopped being the dominant frequency. A different kind of energy moved in: quieter, more technical in a craft sense, more interested in proportion than proclamation. The clothes started to look like decisions again rather than evidence of participation. The best menswear stopped performing “cool” and started performing judgement.

This isn’t simply a mood swing, or a pendulum doing what pendulums do. There are real economic and cultural forces behind it, and they’re aligning in a way that makes menswear feel, for the first time in years, like the most alive part of the fashion conversation. Not because men suddenly discovered taste, but because the system that dressed them is being redesigned — by the market, by culture, and by the people now being hired to steer the biggest houses.

If the streetwear decade trained consumers to chase symbols, the current moment is training them to read signals.

And signals are harder to fake.

The Jonathan Anderson effect

If you want a single, clean indicator that menswear is no longer the side quest, look at where the industry’s biggest chess pieces have moved.

Jonathan Anderson’s tenure at Loewe is one of the clearest luxury transformations of the last decade: a Spanish leather house that once sat politely in the corner of the LVMH portfolio became a cultural engine, an object of obsession, a brand with a point of view. The numbers attached to the Anderson era are frequently cited because they tell the story of what taste can do when it’s consistent enough to become infrastructure. Loewe’s operating company reported 2024 revenue of roughly €885 million; growth continued, but profitability tightened, with net profit down materially in that final year of the era — a reminder that building a modern luxury phenomenon is expensive. The point isn’t the margin. The point is the gravitational pull.

When Anderson was appointed to lead creation at Dior across collections, it read as an industry headline for a reason: Dior wasn’t just hiring a designer. It was consolidating power in someone whose strength has been to make fashion feel intellectually current without losing the ability to sell product. That kind of appointment signals that menswear — and the broader cultural temperature it sets — is now central to luxury strategy, especially in a period when the sector has faced a slower, more cautious consumer mood.

At the same time, Loewe’s succession plan reinforced the message. When Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez were named to replace Anderson, the story wasn’t merely “two Americans take over a European house.” It was that Loewe’s identity — craft, culture, design intelligence — has become valuable enough that the transition itself is treated like state news. You don’t get that kind of attention if the market sees you as a niche handbag brand. You get it when you are understood as a cultural institution with revenue attached.

This is what menswear looks like when it matters: it’s where the prestige appointments land, where the narrative energy flows, and where the industry tests its next decade of identity.

The money is real, even if the definitions argue

Menswear’s creative revival would be interesting even if it were purely aesthetic, but it’s not. The commercial layer matters because it changes what brands are willing to build — and how seriously they take the men’s customer as a long-term relationship rather than a seasonal sale.

Market sizing for menswear varies depending on what’s included — luxury only, total apparel, accessories, footwear, online share, region. Some trackers put the global menswear market in the mid-hundreds of billions; others place it in the low-to-mid six hundreds in 2024 and forecast it reaching the high nine hundreds by the early-to-mid 2030s. The precise number is less important than the direction: menswear is huge, and it’s still growing. The growth isn’t only coming from suits or formal wear. It’s coming from the middle ground: elevated casual, soft tailoring, premium knitwear, quality footwear — the category where men can spend more without feeling like they’re “dressing up.”

That middle ground is where the best creativity lives right now, because it’s where the clothes have to do two jobs: they have to carry taste and survive real life.

The other financial truth is that luxury, in a period of slower consumer confidence, likes predictable customers. Womenswear can be more volatile — more trend-dependent, more seasonal in silhouette shifts. Menswear, when it’s built well, becomes uniform. And uniform is a recurring revenue model disguised as identity.

That’s why the current moment feels structural. Brands aren’t simply making nicer clothes. They’re building systems for how men want to live.

The end of the streetwear bargain

Streetwear’s dominance did something brilliant and something corrosive.

It democratized aspiration. You didn’t need heritage knowledge to participate; you needed timing. It made men’s fashion less about learning and more about access. It also made luxury houses realize they could borrow streetwear’s distribution psychology — scarcity, drops, collaborations — and rebrand it as “culture.”

But the bargain streetwear offered was always temporary. The promise was: wear this, and you inherit a story. Over time, the story became repetitive. Logos inflated until they stopped meaning anything. Collaboration culture turned into a treadmill. When every month is an “event,” nothing is.

The result is a fatigue that looks like sophistication but is really just exhaustion. Consumers didn’t suddenly become more refined. They became less willing to be played.

The funniest part is that the anti-streetwear moment isn’t anti-casual. It’s anti-cynicism. Men still want comfort. They just want it with integrity — and with enough craft to justify the spend.

That’s why the current menswear wave feels less like a trend and more like a moral correction: fewer slogans, more substance; fewer collectibles, more clothes.

Phoebe Philo’s influence without menswear

Phoebe Philo’s return didn’t need to include menswear to reshape it.

Her eponymous brand, launched with a level of scrutiny that only a handful of designers receive, has operated as a kind of atmospheric pressure system. It pushes the industry toward restraint, quality obsession, and the idea that luxury is not a logo but a feeling: weight, drape, proportion, silence. The point isn’t that men are buying her pieces — many are — but that her aesthetic has become the template for a broader rejection of the streetwear decade’s noise.

Philo’s influence in menswear works the way cultural influence always does when it’s real: it isn’t copied directly; it’s translated. It shows up in the return of long coats that feel architectural rather than formal. In trousers that sit with intention. In shoes that don’t scream. In the idea that the most expensive thing can also be the least performative.

In a culture where men are increasingly judged not by what they own but by how they compose a life, that kind of restraint reads as power.

Quiet tailoring, or: the suit that refuses to be a suit

Tailoring is back, but not as a return to office hierarchy. It’s back as a language.

The contemporary suit — in the interesting parts of menswear — is not a uniform of obedience. It’s a tool for shape. Soft shoulders. Longer lines. Wider trousers. Jackets worn open like outerwear. The suit as an arrangement, not a declaration.

This is why the phrase “quiet luxury” only half-explains what’s happening. Quiet luxury implies wealth hiding in plain sight. What’s happening in menswear is slightly different: men are buying their way out of trend dependency. A good coat, a good trouser, a good shoe. Clothes that can survive three years without looking like the moment that produced them has expired.

Brands aligned with this mood — the houses and groups positioned around fabric, touch, and silhouette — have found real commercial traction. Zegna’s flagship brand, for example, has reported around €1.2 billion in annual revenue, driven largely by direct-to-consumer performance and the kind of soft, high-end menswear that looks almost boring until you put it on. Boring, in menswear, is often the highest compliment: it means the clothes are doing the work rather than asking you to do it for them.

The important shift is this: men are no longer paying for spectacle. They’re paying for certainty.

The gorpcore plateau and the uniform impulse

Gorpcore taught the city to dress like it could leave at any moment.

Arc’teryx shells, Salomon trail runners, technical fleece: clothing that implied capability. It was a perfect pandemic and post-pandemic language — resilience, preparedness, competence. It was also, inevitably, destined to become uniform. Once everyone speaks a style language, it stops being a signifier and becomes background noise.

The next impulse looks less like outdoors and more like work.

Workwear, uniform culture, the aesthetics of labour: chore coats, carpenter pants, heavy denim, factory greys. It’s not cosplay for most wearers; it’s a way to signal seriousness in a period when “hype” feels adolescent. A workwear silhouette says: I’m not here to perform cool. I’m here to last.

This is one reason menswear is interesting again: the category is rediscovering the poetry of function. Not the performative function of technical gear, but the honest function of garments built for repetition.

Japanese influence and the return of texture

Another quiet driver of the menswear renaissance is Japan’s long-standing insistence that texture is culture.

Japanese menswear’s influence has never been about “trends” so much as methods: fabric development, dyeing, finishing, the romance of process. Brands that treat clothing as an object worth studying — not just wearing — have shaped how men think about value. You see it in the global appetite for brushed cottons, dense wools, roomy silhouettes, imperfect finishes, and clothing that looks better after a year of use.

This is also why platforms and retailers matter more than ever. The modern menswear customer is educated by distribution: concept stores, online curators, editorial e-commerce. A man in New York can buy into Tokyo’s sensibility without boarding a plane. A London buyer can discover a brand through a single well-shot product page and fall into a rabbit hole.

The internet didn’t kill menswear culture. It turned it into a global classroom.

The geography of the new menswear

If this were 2015, we’d say “menswear is happening in London” and gesture at a few designers. That’s no longer accurate.

Paris remains the centre of luxury theatre — the place where power brands stage their worldview. Milan remains the engine room of tailoring and material excellence, increasingly rewritten by designers who understand that formality must be flexible. London is still a laboratory, but its strength is now less about runway spectacle and more about street intelligence and education pipelines.

Tokyo is the most sophisticated consumer market for menswear because it treats clothing as culture, not content. Seoul continues to fuse fashion with music and grooming at an industrial scale — and it has taught luxury how men move through image ecosystems. Meanwhile, Lagos and Accra are building a different kind of menswear energy: tailoring that treats identity as material, not just silhouette.

The important point is not “globalism.” It’s distribution of taste. Menswear’s creativity is no longer concentrated. It’s networked.

When taste becomes networked, novelty accelerates — and the houses that survive are the ones with real point of view, not just marketing.

The new menswear consumer

The modern menswear buyer is no longer a niche. He’s a market with habits.

He shops online. He cross-references. He reads. He watches. He learns fabric names, production origins, the difference between a brand that designs and a brand that licenses. He buys fewer things, but better things — or he buys many things, but with a curator’s sense of coherence. Even the ones who say they “don’t care” are often performing a kind of care through uniform choices.

This buyer is also more willing to spend on self-presentation. Not just clothing, but grooming, skincare, fragrance, hair. Menswear is benefitting from a broader cultural permission: men can invest in appearance without having to justify it as vanity. It’s framed as professionalism, wellness, identity, or simply adulthood.

Streetwear opened the door. Quiet tailoring is furnishing the house.

The tension: why this renaissance could wobble

If menswear feels creatively alive, it also exists inside a luxury market that is not uniformly healthy.

The broader sector has experienced a slowdown, particularly in parts of Asia, and even high-growth brands have shown that expansion can strain profitability. Loewe’s 2024 revenue growth came alongside a significant profit drop — a reminder that cultural dominance doesn’t guarantee easy margins. The industry’s creative reshuffles — Dior, Loewe, Gucci and beyond — are not happening in a vacuum. They are responses to a more cautious consumer environment and the need to reignite desire without relying on cheap tricks.

There’s also the cliché risk. Quiet luxury can become a uniform too. “Anti-logo” can turn into just another badge. If everyone starts dressing in beige cashmere and long coats, the look stops reading as discernment and starts reading as compliance.

Fast fashion, meanwhile, is still the volume engine of the world. It can replicate silhouettes quickly, even if it cannot replicate quality. The danger for menswear’s renaissance is that it becomes a surface language divorced from its material soul.

The question is whether men are buying into a new worldview — or simply borrowing the costume.

What happens next

The most convincing sign that menswear is entering a new creative era is not a single collection or a single appointment. It’s the coherence of the system shift.

The streetwear decade taught the industry how to manufacture desire through scarcity and spectacle. The current decade is teaching it something harder: how to build desire through consistency, craft and credibility.

Anderson moving upward in the luxury hierarchy, Loewe’s succession being treated as major cultural news, the market strength of soft tailoring, the rise of a post-hype sensibility, the return of texture and proportion — these are not isolated signals. They describe an ecosystem resetting its values.

Menswear is suddenly interesting again because it stopped trying to be “cool” in the loud way.

It started trying to be good.

And when men start dressing for taste rather than attention — when they start choosing clothes that hold up under time rather than under likes — the entire industry has to become more creative, not less, because the tricks stop working.

In the end, the renaissance isn’t about suits or sneakers, minimalism or maximalism.

It’s about meaning returning to the surface of the garment.

After a decade of hype, menswear is remembering how to speak.

Wills Mayani writes for LocoWeekend. For more, subscribe.